|

|

|

| OR |

|

|

|

Books Featuring

Coomaraswamy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy’s life and work

|

|

A. K. Coomaraswamy’s biography, photos, film clips, online articles, slideshows, bibliography, links, more

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy (1877-1947) was one of the great art historians of the twentieth century whose multifaceted writings deal primarily with visual art, aesthetics, literature and language, folklore, mythology, religion, and metaphysics. His most mature works adeptly expound the perspective of the perennial philosophy by drawing on a detailed knowledge of the arts, crafts, mythologies, cultures, folklores, symbolisms, and religions of both the East and the West. Along with René Guénon and Frithjof Schuon, Ananda Coomaraswamy is considered as a leading member of the Traditionalist or Perennialist school of comparative religious thought.

Born in Ceylon in 1877 of a Tamil father and an English mother, Coomaraswamy was brought up in England following the early death of his father. He was educated at Wycliffe College and at London University where he studied botany and geology. As part of his doctoral work Coomaraswamy carried out a scientific survey of the mineralogy of Ceylon and seemed poised for an academic career as a geologist. However, under pressure from his experiences while engaged in his fieldwork, he became absorbed in a study of the traditional arts and crafts of Ceylon and of the social conditions under which they had been produced. In turn he became increasingly distressed by the corrosive effects of British colonialism.

In 1906 Coomaraswamy founded the Ceylon Social Reform Society of which he was the inaugural President and moving force. The Society addressed itself to the preservation and revival not only of traditional arts and crafts but also of the social values and customs which had helped to shape them. The Society also dedicated itself, in the words of its Manifesto, to discouraging “the thoughtless imitation of unsuitable European habits and custom.”[1] Coomaraswamy called for a re-awakened pride in Ceylon’s past and in her cultural heritage. The fact that he was half-English in no way blinkered his view of the impoverishment of national life brought by the British presence in both Ceylon and India.

In the years between 1900 and 1913 Coomaraswamy moved backwards and forwards between Ceylon, India, and England. In India he formed close relationships with the Tagore family and was involved in both the literary renaissance and the swadeshi movement. All the while in the subcontinent he was researching the past, investigating arts and crafts, uncovering forgotten and neglected schools of religious and court art, writing scholarly and popular works, lecturing, and organizing bodies such as the Ceylon Social Reform Society and, in England, the India Society.

In England he found his own social ideas anticipated in the work of William Blake, John Ruskin, and William Morris, three of the foremost representatives of a fiercely eloquent and morally impassioned current of anti-industrialism. Such figures had elaborated a biting critique of the ugliest and most dehumanizing aspects of the industrial revolution and of the acquisitive commercialism which increasingly polluted both public and private life. They believed the new values and patterns of urbanization and industrialization were disfiguring the human spirit. These writers protested vehemently against the conditions in which many were forced to carry out their daily work and living. Ruskin and Morris, in particular, were appalled by the debasing of standards of craftsmanship and of public taste. Coomaraswamy picked up a catch-phrase of Ruskin’s which he was to mobilize again and again in his own writings: “industry without art is brutality.” The Arts and Crafts Movement of the Edwardian era was, in large measure, stimulated by the ideas of William Morris, the artist, designer, poet, medievalist and social theorist. Morris’ work influenced Coomaraswamy decisively in this period and he involved himself with others in England who were trying to put some of Morris’ ideas into practice. The Guild and School of Handicraft, with which Coomaraswamy had some connections, was a case in point. Later in life Coomaraswamy turned less often to explicitly social and political questions. By then he had become aware that “politics and economics, although they cannot be ignored, are the most external and least part of our problem.”[2]

Closely related to his interest in social questions was his work as an art historian. From the outset Coomaraswamy’s interest in art was controlled by much more than either antiquarian or “aesthetic” considerations. For him the most humble folk art and the loftiest religious creations alike were an outward expression not only of the sensibilities of those who created them but of the whole civilization in which they were nurtured. There was nothing of the art nouveau slogan of “art for art’s sake” in Coomaraswamy’s outlook. His interest in traditional arts and crafts, from a humble pot to a Hindu temple, was always governed by the conviction that something immeasurably precious and vitally important was disappearing under the onslaught of modernism in its many different guises. Coomaraswamy’s achievement as an art historian can perhaps best be understood in respect of three of the major tasks which he undertook: the “rehabilitation” of Asian art in the eyes of Europeans and Asians alike; the massive work of scholarship which he pursued as curator of the Indian Section of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; the penetration and explanation of traditional views of art and their relationship to philosophy, religion, and metaphysics.

In assessing Coomaraswamy’s achievement it needs to be remembered that the conventional attitude of the Edwardian era towards the art of Asia was, at best, condescending, and at worst, frankly contemptuous. Asian art was often dismissed as “barbarous,” “second-rate”, and “inferior” and there was a good deal of foolish talk about “eight-armed monsters” and the like.[3] In short, there was, in England at least, an almost total ignorance of the sacred iconographies of the East. Such an artistic illiteracy was coupled with a similar incomprehension of traditional philosophy and religion, and buttressed by all manner of Eurocentric assumptions. Worse still was the fact that such attitudes had infected the Indian intelligentsia, exposed as it was to Western education and influences.

Following the early days of his fieldwork in Ceylon, Coomaraswamy set about dismantling these prejudices through an affirmation of the beauty, integrity, and spiritual density of traditional art in Ceylon and India and, later, in other parts of Asia. He was bent on the task of demonstrating the existence of an artistic heritage at least the equal of Europe’s. He not only wrote and spoke and organized tirelessly to educate the British but he scourged the Indian intelligentsia for being duped by assumptions of European cultural superiority. In studies like Medieval Sinhalese Art (1908), The Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon (1913), and his earliest collection of essays, The Dance of Shiva (1918), Coomaraswamy combated the prejudices of the age and reaffirmed traditional understandings of Indian art. He revolutionized several specific fields of art history, radically changed others. His work on Sinhalese arts and crafts and on Rajput painting, though they can now be seen as formative in the light of his later work on Buddhist iconography and on Indian, Platonic, and Christian theories of art, were nevertheless early signs of a stupendous scholarship. His influence was not only felt in the somewhat rarefied domain of art scholarship but percolated into other scholarly fields and eventually must have had some influence on popular attitudes in Ceylon, India, England, and America.

As a Curator at the Boston Museum from 1917 onwards, Coomaraswamy performed a mighty labor in classifying, cataloguing, and explaining thousands of items of oriental art. Through his professional work, his writings, lectures, and personal associations Coomaraswamy left an indelible imprint on the work of many American galleries and museums and influenced a wide range of curators, art historians, orientalists, and critics—Stella Kramrisch, Walter Andrae, and Heinrich Zimmer to name a few of the more well-known. Zimmer wrote of Coomaraswamy: “the only man in my field who, whenever I read a paper of his, gives me a genuine inferiority complex.”

Traditional art, in Coomaraswamy’s view, was always directed towards a twin purpose: a daily utility, towards what he was fond of calling “the satisfaction of present needs,” and to the preservation and transmission of moral values and spiritual teachings derived from the tradition in which it appeared. A Tibetan thanka, a medieval cathedral, a Red Indian utensil, a Javanese puppet, a Hindu deity image—in such artifacts and creations Coomaraswamy sought a symbolic vocabulary. The intelligibility of traditional arts and crafts, he insisted, does not depend on a more or less precarious recognition, as does modern art, but on legibility. Traditional art does not deal in the private vision of the artist but in a symbolic language. By contrast modern art, which from a traditionalist perspective includes Renaissance and, generally speaking, all post-Renaissance art, is divorced from higher values, tyrannized by the mania for “originality,” controlled by aesthetic and sentimental considerations, and drawn from the subjective resources of the individual artist rather than from the well-springs of tradition. The comparison, needless to say, does not reflect well on modern art! An example: “Our artists are ‘emancipated’ from any obligation to eternal verities, and have abandoned to tradesmen the satisfaction of present needs. Our abstract art is not an iconography of transcendental forms but the realistic picture of a disintegrated mentality.”[4]

During the late 1920s Coomaraswamy’s life and work somewhat altered their trajectory. The collapse of his third marriage, ill-health and a growing awareness of death, an impatience with the constrictions of purely academic scholarship, and the influence of René Guénon all co-operated to deepen Coomaraswamy’s interest in spiritual and metaphysical questions. He became more austere in his personal lifestyle, partially withdrew from the academic and social worlds in which he had moved freely over the last decade, and addressed himself to the understanding and explication of traditional metaphysics, especially those of classical India and pre-Renaissance Europe. Coomaraswamy remarked in one of his letters that “my indoctrination with the Philosophia Perennis is primarily Oriental, secondarily Mediaeval, and thirdly Classic.”[5] His later work is densely textured with references to Plato and Plotinus, Augustine and Aquinas, Eckhart and the Rhineland mystics, to Shankara and Lao-tzu and Nagarjuna. He also explored folklore and mythology since these too carried profound teachings. Coomaraswamy remained the consummate scholar but his work took on a more urgent nature after 1932. He spoke of his “vocation”—he was not one to use such words lightly—as “research in the field of the significance of the universal symbols of the Philosophia Perennis” rather than as “one of apology for or polemic on behalf of doctrines.”[6]

The influence of Guénon was decisive. Coomaraswamy discovered Guénon’s writings through Heinrich Zimmer some time in the late 1920s and, a few years later wrote, “no living writer in modern Europe is more significant than René Guénon, whose task it has been to expound the universal metaphysical tradition that has been the essential foundation of every past culture, and which represents the indispensable basis for any civilization deserving to be so-called.”[7] Coomaraswamy told one of his friends that he and Guénon were “entirely in agreement on metaphysical principles” which, of course, did not preclude some divergences of opinion over the applications of these principles on the phenomenal plane.[8]

The vintage Coomaraswamy of the later years is to be found in his masterly works on Vedanta and on the Catholic scholastics and mystics. There is no finer exegesis of traditional Indian metaphysics than is to be found in these later works. His work on the Platonic, Christian, and Indian conceptions of sacred art is also unrivalled. Some of Coomaraswamy’s finest essays on these subjects are brought together in Coomaraswamy, Vol. II: Selected Papers, Metaphysics, edited by Roger Lipsey. Special mention should be made of “The Vedanta and Western Tradition,” “Sri Ramakrishna and Religious Tolerance,” “Recollection, Indian and Platonic,” “On the One and Only Transmigrant”, and “On the Indian and Traditional Psychology, or Rather Pneumatology.” But it hardly matters what one picks up from the later period: all his mature work is stamped with rare scholarship, elegant expression, and a depth of understanding which makes most of the other scholarly work on the same subjects look vapid and superficial. Of his later books three in particular deserve much wider attention: Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art (1939), Hinduism and Buddhism (1943) and Time and Eternity (1947). The Bugbear of Literacy (1979) (first published in 1943 as Am I my Brother’s Keeper?) and two posthumous collections of some of his most interesting and more accessible essays, Sources of Wisdom (1981) and What is Civilization? (1989), offer splendid starting-points for uninitiated readers. We can hardly doubt that the life and work of this “warrior for dharma”[9] was a precious gift to all those interested in the ways of the spirit.

In 1947 Coomaraswamy intended to retire from his position as Curator at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in order to return to India, where he planned to complete a new translation of the Upanishads and take on sannyasa (renunciation of the world). These plans, however, were cut short by his sudden and untimely death.

Adapted from Harry Oldmeadow, Journeys East: 20th Century Western Encounters with

Eastern Religious Traditions (Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2004), pp. 194-202.

NOTES

[1] Manifesto of the Ceylon Reform Society, almost certainly written by Coomaraswamy, quoted in Roger Lipsey, Coomaraswamy, Vol. 3: His Life and Work (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978), p. 22.

[2] A.K. Coomaraswamy quoted in Dale Riepe, Indian Philosophy and Its Impact on American Thought (Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1970), p. 126.

[3] Lipsey, Coomaraswamy, Vol. 3: His Life and Work, pp. 60-61.

[4] “Symptom, Diagnosis and Regimen” in Coomaraswamy, Vol.1: Selected Papers: Traditional Art and Symbolism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978), pp. 316-317.

[5] Letter to Artemus Packard, May 1941, in Selected Letters of Ananda Coomaraswamy, edited by Alvin Moore, Jr. and Rama Coomaraswamy (New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Center, 1988), p. 299.

[6] A.K. Coomaraswamy, “The Bugbear of Democracy, Freedom and Equality,” Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1977, p. 134.

[7] Quoted in Lipsey, Coomaraswamy, Vol. 3: His Life and Work, p. 170.

[8] Whitall Perry, “The Man and the Witness,” in S.D.R. Singam (ed.), Ananda Coomaraswamy: Remembering and Remembering Again and Again (Kuala Lumpur: privately published, 1974), p. 5.

[9] Marco Pallis, “A Fateful Meeting of Minds,” Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 12, Nos. 3, 4, 1978, p. 187.

|

The Wisdom of Ananda Coomaraswamy: Selected Reflections on Indian Art, Life, and Religion, edited by S. Durai Raja Singam and Joseph A. Fitzgerald, November 2011.

The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, edited by Rama P. Coomaraswamy, 2003.

Figures of Speech or Figures of Thought? The Traditional View of Art, Revised Edition with Previously Unpublished Author’s Notes, edited by William Wroth, 2007.

“The Bugbear of Freedom, Equality, and Democracy”, in The Betrayal of Tradition: Essays on the Spiritual Crisis of Modernity, edited by Harry Oldmeadow, 2005.

“A Figure of Speech or a Figure of Thought?” and “The Christian and Oriental, or True, Philosophy of Art”, in Every Man An Artist: Readings in the Traditional Philosophy of Art, edited by Brian Keeble, 2005.

“Paths That Lead to the Same Summit”, in Ye Shall Know the Truth: Christianity and the Perennial Philosophy, edited by Mateus Soares de Azevedo, 2005.

“The Vedanta and Western Tradition” and “Sri Ramakrishna and Religious Tolerance”, in Light From the East: Eastern Wisdom for the Modern West, edited by Harry Oldmeadow, 2007.

“Symplegades”, in The Underlying Religion: An Introduction to the Perennial Philosophy, edited by Martin Lings and Clinton Minnaar, 2007. |

|

|

|

|

| The Aims of Indian Art | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Winter, 1975) | Coomaraswamy, Ananda | | Art, Hinduism, Modernism, Symbolism, Tradition |

|

|

|

| Symplegades | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 7, No. 1. (Winter, 1973); also in the book "The Underlying Religion" | Coomaraswamy, Ananda | | Comparative Religion, Mythology or Legend, Symbolism |

|

|

|

| The Influence of Greek on Indian Art | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 8, No. 1. (Winter, 1974) | Coomaraswamy, Ananda | | Art, Modernism, Symbolism, Tradition |

|

|

|

| The Nature of Medieval Art | The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy | Coomaraswamy, Ananda | | Art, Modernism, Symbolism, Tradition |

|

|

|

| The Interpretation of Symbols | The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy | Coomaraswamy, Ananda | | Art, Comparative Religion, Symbolism, Tradition |

|

|

|

In this two-part essay, A.K. Coomaraswamy sets out to prove "that our use of the term 'aesthetic' forbids us also to speak of art as pertaining to the 'higher things of life' or the immortal part of us; that the distinction of 'fine' from 'applied' art, and corresponding manufacture of art in studios and artless industry in factories, takes it for granted that neither the artist nor the artisan shall be a whole man.…" Using primarily Platonic and Hindu sources, he shows quite convincingly that modern arts education and production may result in an endless variety of arts for leisure, but that this situation encourages neither the understanding of traditional art, nor the production of arts that are "effective" in ennobling people with those "higher things of life."

| “A Figure of Speech, or a Figure of Thought?” (Part 2) | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 6, No. 2. (Spring, 1972) | Coomaraswamy, Ananda | | Art, Modernism, Perennial Philosophy, Platonism, Tradition |

|

|

|

In this two-part essay, A.K. Coomaraswamy sets out to prove "that our use of the term 'aesthetic' forbids us also to speak of art as pertaining to the 'higher things of life' or the immortal part of us; that the distinction of 'fine' from 'applied' art, and corresponding manufacture of art in studios and artless industry in factories, takes it for granted that neither the artist nor the artisan shall be a whole man.…" Using primarily Platonic and Hindu sources, he shows quite convincingly that modern arts education and production may result in an endless variety of arts for leisure, but that this situation encourages neither the understanding of traditional art, nor the production of arts that are "effective" in ennobling people with those "higher things of life."

| “A Figure of Speech, or a Figure of Thought?” (Part 1) | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 6, No. 1. (Winter, 1972) | Coomaraswamy, Ananda | | Art, Modernism, Perennial Philosophy, Platonism, Tradition |

|

|

|

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy explores the innocent-sounding question "Why exhibit works of art?" Beyond the task of protecting valuable relics, exhibiting works of art must have an educational purpose. In delving into the significance of this purpose, Coomaraswamy covers topics such as the vanity of much of modern art, the necessity of understanding the techniques and uses of ancient art (going beyond the limitations of our own modern psychology and aesthetics), the Platonic view of the arts, and more. This well structured discussion is an excellent primer on the Traditionalist/Perennialist view on the meaning of "art" and its proper usages in real, everyday lives outside of the confines of a museum.

| Why Exhibit Works of Art? | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 5, No. 3. ( Summer, 1971) | Coomaraswamy, Ananda | | Art, Comparative Religion, Perennial Philosophy, Spiritual Life, Symbolism, Tradition |

|

|

|

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy reveals the symbolism of archery that underlies this seemingly mundane sport. He describes its original function in initiation ceremonies of disciples, across a number of traditions, as they dedicated themselves to their spiritual paths. The author sums up the essay with the observations that "one sees how in a traditional society every necessary activity can be also the Way, and that in such a society there is nothing profane; a condition the reverse of that to be seen in secular societies, where there is nothing sacred. We see that even a "sport" may also be a yoga, and [that] the active and contemplative lives, outer and inner man can be unified in a single act of being in which both selves cooperate."

| The Symbolism of Archery | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 5, No. 2. ( Spring, 1971) | Coomaraswamy, Ananda | | Comparative Religion, Esoterism, Mythology or Legend, Perennial Philosophy, Spiritual Life, Symbolism |

|

|

|

A. K. Coomarawamy's address, here as an essay, on Sri Ramakrishna is less biography than an illustration of how a study of religious diversity can, and should, result in an enriched understanding of one's own religious tradition and path to salvation.

| Sri Ramakrishna and Religious Tolerance | The online library of articles at religioperennis.org | Coomaraswamy, Ananda | | Comparative Religion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Coomaraswamy is an extremely precious author.”

—Frithjof Schuon, author of The Transcendent Unity of Religions

“Over sixty years have passed since the death of Ananda Coomaraswamy; yet his writings remain as pertinent today as when he wrote them and his voice echoes in the ears of present day seekers of truth and lovers of traditional art as it did a generation ago. In contrast to most scholarly works which become outmoded and current philosophical opuses which become stale, Coomaraswamy’s works possess a timeliness which flows from their being rooted in the eternal present.”

—Seyyed Hossein Nasr, University Professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University, and author of Islam : Religion, History, and Civilization and The Heart of Islam: Enduring Values for Humanity

“Ananda Coomaraswamy is in many ways to me a model: the model of one who has thoroughly and completely united in himself the spiritual tradition and attitudes of the Orient and of the Christian West.”

—Thomas Merton, author of The Seven Storey Mountain and New Seeds of Contemplation

“Coomaraswamy’s essays [give] us a view of his scholarship and brilliant insight.”

—Joseph Campbell, author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces and The Masks of God

“[Ananda Coomaraswamy is] that noble scholar upon whose shoulders we are still standing.”

—Heinrich Zimmer, author of The King and the Corpse and Philosophies of India

“[Coomaraswamy] is one of the most learned and creative scholars of the century.”

—Mircea Eliade, scholar, author, and editor-in-chief of Macmillan’s Encyclopedia of Religion

“The mythological content of the arts he was pursuing fascinated Coomaraswamy and inspired him—with his inborn universal genius, similar to, though differently oriented, from Guénon’s—to see and reveal the striking homogeneity of mythical patterns in traditions having the most diverse outward characters.”

—Whitall N. Perry, author of A Treasury of Traditional Wisdom

“Coomaraswamy uncovers and puts before us the truths of a primordial tradition, reflected in the world’s existing traditions and expressed by them as if in differing dialects. He asks us to join him in the effort to decipher the religiously rich arts and crafts, literatures and folklore of the world’s traditions.”

—Roger Lipsey, author of Coomaraswamy, Vol. 1: His Life and Work

“Coomaraswamy’s work is as important as that of Joseph Campbell or Carl Jung, and deserving of the same attention.”

—David Frawley, author of Yoga and Ayurveda

“Ananda Coomaraswamy is best known as one of the twentieth century’s most erudite and percipient scholars of the sacred arts and crafts of both East and West. He also had few peers in the exegesis of traditional philosophy and metaphysics.”

—Harry Oldmeadow, La Trobe University Bendigo, author of Traditionalism: Religion in the Light of the Perennial Philosophy

“One of the great exponents of traditional thought in the 20th century, Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy combined in his impressive scholarship the mathematical and aesthetic virtues of sublime height, expansive range, and penetrating depth, all encompassed within a precise and harmonious symmetry. The illuminating references and footnotes in his eloquent writings are a veritable treasure-trove for scholars and seekers alike, evidencing these virtues, and one comes away from his works with the sense of a visionary mind focused on the inexpressible reality of which all the great wisdom traditions speak.”

—M. Ali Lakhani, editor of the journal Sacred Web

“Ananda K. Coomaraswamy is in the very first rank of exceptional men, such as René Guénon and Frithjof Schuon, who in our ‘dark age’ have permitted us to rediscover the great truths of sacred Tradition, to relearn what a civilization, a society, and a world are that conform to this Tradition. . . . The masterful work of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy is one of the most suitable to enlighten the minds and hearts of ‘men of good will.’”

—Jean Hani, author The Symbolism of the Christian Temple

“Coomaraswamy’s essays, learned, elegant, and wise, are one of the great treasures of twentieth-century thought. To read them is to see the world in the clear light of tradition, to understand art and philosophy from the viewpoint of first principles, to be reminded of our sacred calling and of the One who calls us.”

—Philip Zaleski, editor of The Best Spiritual Writing series

“It must be said that Coomaraswamy can only be read with profit by those who wish to take thinking seriously. He wrote as if it were possible to restore true civilization on the basis of the corrective of a return to the metaphysical wisdom of the timeless traditions. To combat error, by going to its root cause, as armed with these studies one certainly can do, is already to take a step towards the only safe ground beyond the abyss that immediately faces us.”

—Brian Keeble, editor of Every Man An Artist

“Like St. Augustine, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy wrote in order to perfect his own understanding. He sought to know the whatness and principial roots of things, above all of himself. In doing so, he collaterally provided access to a fundamental intellectual itinerary which unfailingly beckons all who recognize in themselves an intrinsic regard for Truth.”

—Alvin Moore, Jr., co-editor of Selected Letters of Ananda Coomaraswamy

“After having read Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, the distinction between Oriental and Occidental thought hardly has any more meaning. He is a tireless ‘ferryman’ between one and the other side of the same transcendent [reality].”

—Jean Canteins, author

“The pioneering and interdisciplinary essays of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy on medieval Christian and Oriental art have shed so much light on religious symbolism and iconography, and given such profound metaphysical insight into the study of aesthetics and traditional folklore, that if contemporary art history does not take [his] challenges and contributions into account, it will inevitably fall prey to ideological reductionisms and

degrade the ancient and perennial language of art forms into a mere archaic system of lifeless symbols with [no] meaning.”

—Ramon Mujica Pinilla, art historian, Universidad Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru

“Slow and erudite meditations on the self-luminosity of the Spirit, Coomaraswamy’s works allow us to penetrate the heart of Indian Gnosis for which we are but waves on the surface of the divine substance, but rays emanated from the sun of Goodness. Coomaraswamy shares with us a sensitivity to sacred art in its multiple dimensions, an art he always filters through the wisdom of Plato and the Upanishads.”

—Patricia Reynaud, Miami University, Ohio, and co-founder of religioperennis.org

“In Coomaraswamy . . . all the religious traditions of the world meet.”

—Jean Borella, author of The Secret of the Christian Way and The Sense of the Supernatural

“Others have written the truth about life and religion and man’s work. Others have written good clear English. Others have had the gift of witty exposition. Others have understood the metaphysics of Christianity and others have understood the metaphysics of Hinduism and Buddhism. Others have understood the true significance of erotic drawings and sculptures. Others have seen the relationships of the true and the good and the beautiful. Others have had apparently unlimited learning. Others have loved; others have been kind and generous. But I know of no one else in whom all these gifts and all these powers have been combined. . . . I believe that no other living writer has written the truth in matters of art and life and religion and piety with such wisdom and understanding.”

—Eric Gill, sculptor and typeface designer

|

|

|

|

| A Fateful Meeting of Minds: A. K. Coomaraswamy and René Guénon | The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy | Pallis, Marco | | Coomaraswamy, A.K., Guénon, René, History, Perennial Philosophy, Tradition |

|

|

|

Roger Lipsey discusses the philosopher Ananda Coomaraswamy. Lipsey uses Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of each individual being comprised of an outer and an inner man, “man and the Man in this man”, and uses this to examine Coomaraswamy’s life through his search for self-knowledge. Thus in discussing his philosophies and his search for truth, we can better understand him.

| The Two Selves: Coomaraswamy as Man and Metaphysician | Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 6, No. 4. (Autumn, 1972) | Lipsey, Roger | | Coomaraswamy, A.K., Esoterism, Spiritual Life |

|

|

|

| Introduction to Figures of Speech or Figures of Thought? | Figures of Speech or Figures of Thought: The Traditional View of Art | Lipsey, Roger | | Art |

|

|

|

| Editor's Preface to Figures of Speech or Figures of Thought? | Figures of Speech or Figures of Thought: The Traditional View of Art | Wroth, William | | Biography |

|

|

|

| A Fateful Meeting of Minds: A. K. Coomaraswamy and R. Guénon | The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy | Pallis, Marco | | Biography |

|

|

|

| Introduction to The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy | The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy | Coomaraswamy, Rama P. | | Biography |

|

|

|

| Foreword to The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy | The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy | Sharma, Arvind | | Tradition |

|

|

|

| Ananda K. Coomaraswamy: Scholar of the Spirit | The Essential Sophia: The Journal of Traditional Studies | Keeble, Brian | | Tradition |

|

|

|

|

8 entries

(Displaying results 1 - 8)

|

View : |

|

Jump to: |

|

Page:

[1]

of 1 pages

|

|

|

Loading... |

|

|

|

|

|

Books in English

The Deeper Meaning of the Struggle. Broad Campden: Essex House Press, 1907.

Mediaeval Sinhalese Art. Broad Campden: Essex House Press, 1908.

The Aims of Indian Art. 1908.

The Message of the East. Madras: Ganesh Press, 1908.

Essays in National Idealism. Colombo: Colombo Apothecaries Co. Ltd., 1909.

The Indian Craftsman. London: Probsthain, 1909.

Indian Drawings. London: Essex House Press, 1910.

Selected Examples of Indian Art. Broad Campden: Essex House Press, 1910.

Art and Swadeshi. Madras: Ganesh Press, 1911.

Indian Drawings: 2nd Series, Chiefly Rajput. London: Essex House Press, 1912.

The Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon. Edinburgh: Foulis, 1913.

Bronzes from Ceylon: Chiefly in the Colombo Museum. 1914.

Myths of the Hindus and Buddhists, with Sister Nivedita. London: Harrap, 1913.

Vishvakarma: Examples of Indian Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Handicraft. London: Luzac, 1912-14.

Buddha and the Gospel of Buddhism. New York: Putnam, 1916.

Rajput Painting, 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press, 1916.

The Mirror of Gesture: Being the Abhinaya Darpana of Nandikesvara, translated by A. K. Coomaraswamy and Gopala Kristnayya Duggirala. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1917.

The Dance of Siva. New York: Sunwise Turn Press, 1918.

Catalogue of the Indian Collections in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Part I: General Introduction, Part II: Sculpture. Boston: Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1923.

Introduction to Indian Art. Madras: Theosophical Publishing House, 1923.

Catalogue of the Indian Collections in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Part 4: Jaina Paintings and Manuscripts. Boston: Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1924.

Bibliographies of Indian Art. Boston: Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1925.

Catalogue of the Indian Collections in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Part 5: Rajput Painting. Boston: Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1927.

History of Indian and Indonesian Art. Leipzig: Karl W. Hiesemann, 1927.

The Origin of the Buddha Image. Art Bulletin, IX, 4, 1927.

Yaksas, I. Washington: Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 1928.

Catalogue of the Indian Collections in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Part 6: Mughal Painting. Boston: Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1930.

Yaksas, II. Washington: Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 1931.

Introduction to the Art of Eastern India. 1932.

A New Approach to the Vedas: An Essay in Translation and Exegesis. London: Luzac, 1933.

The Transformation of Nature in Art. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1934.

Elements of Buddhist Iconography. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1935.

Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power in the Indian Theory of Government. New Haven, Connecticut: American Oriental Society, 1942.

Hinduism and Buddhism. New York: Philosophical Library, 1943.

Why Exhibit Works of Art? London: Luzac, 1943.

Figures of Speech or Figures of Thought: Collected Essays on the Traditional or “Normal” View of Art. London: Luzac, 1946.

The Religious Basis of the Forms of Indian Society. 1946.

Am I My Brother's Keeper? New York: The John Day Company, 1947.

Time and Eternity. Ascona, Switzerland: Artibus Asiae, 1947.

The Living Thoughts of Gotama The Buddha, with I. B. Horner. London: Cassel, 1948.

Selected Papers I: Traditional Art and Symbolism, edited by Roger Lipsey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

Selected Papers II: Metaphysics, edited by Roger Lipsey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

On the Traditional Doctrine of Art. Ipswich: Golgonooza Press, 1977.

The Bugbear of Literacy. London: Perennial Books, 1979.

Sources of Wisdom. Colombo: Ministry of Cultural Affairs, 1981.

Selected Letters of Ananda Coomaraswamy, edited by Rama P. Coomaraswamy and Alvin Moore, Jr. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

What is Civilization? And Other Essays, edited by Rama P. Coomaraswamy. Ipswich: Golgonooza Press, 1989.

The Door in the Sky: Coomaraswamy on Myth and Meaning, edited by Rama Coomaraswamy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Wisdom of Ananda Coomaraswamy, edited by S.D.R. Singam. Varanasi: Indica, 2001.

The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, edited by Rama P. Coomaraswamy. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2003.

Guardians of the Sundoor: Late Iconographic Essays, edited by Robert Strom. Louisville, KY: Fons Vitae, 2005.

|

|

|

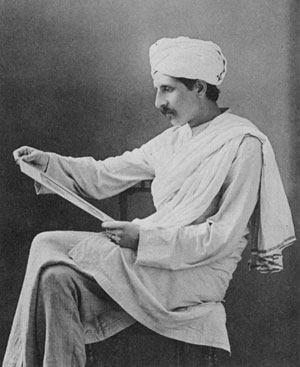

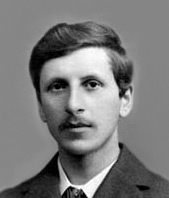

A photo of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy that was once captioned "Coomaraswamy in India, ca. 1909: The young rasika" [Sanskrit: a lover of arts and music] |

| |

|

|

|

photo of the young Ananda K. Coomaraswamy |

|

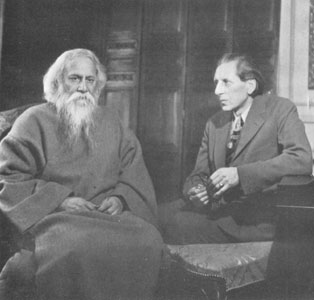

photo of A.K. Coomaraswamy in mid-life, possibly taken in the U.S. |

| |

|

photo of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy with Rabindranath Tagore about 1930

|

| |

|

|

|

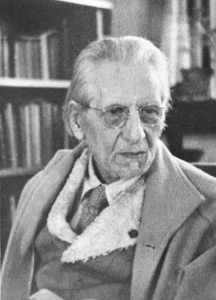

photo of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy in his study in later years

|

|

photo of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy in his beloved garden

|

| |

|

|

•

Coomaraswamy often referred to the philosophia perennis. This slideshow will help readers understand the concept of the perennial philosophy.

A Definition of the Perennial Philosophy

|

•

Along with symbolism, the central theme of Coomaraswamy's early work is sacred art. Read this slideshow to learn more about it.

What is Sacred Art?

|

|

|

A very recent and welcome online contribution is the web site of the Coomaraswamy Library, maintained by a descendant of Ananda K. and Rama P. Coomaraswamy. It is a "private library of the combined lifetime collections of Sir Muthu, Ananda, and Rama Coomaraswamy containing over 15,000 books, pamphlets, periodicals, and recordings as well as selected letters and notes. With many rare and out of print books dating back to the 1600’s, the scope of the library is predominantly Traditional Catholic in nature and geared toward pre-Vatican II liturgical studies and mystical theology. However, a third of the collection focuses on comparative studies and the Sophia Perennis and includes exhaustive selections on Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, and Native American religions." The site has sections of biography on the above-mentioned luminaries of the family, wonderful old photos of traditional scenes, and other images of traditional design. The sections that will be of particular interest to scholars, the catalogues of printed and recorded material, are presently under construction. This site should prove to be an important addition to Traditionalist resources. |

|

A fascinating piece titled "Ananda K. Coomaraswamy: From geology to philosophia perennis," written by Rasoul Sorkhabi, appeared in the February 10, 2008 issue of Current Science. Click here to read this pdf version of the article. It covers his life and career, and even has a good section on AKC's thoughts on the Perennial Philosophy. Most surprising, however, is the summary of his contributions to geology, rarely covered in any depth anywhere else.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|